“You” is the most important word in Christian prayer.

Wait a second. “You”? What about “God”? What about “Christ”? What about “Jesus”? Yes, these are important words in Christian prayer, and the name “Jesus” certainly has its magnificent and eternal power, but I think that the second person pronoun, “You”, is the most important word that we can pray because of what it represents and where it places our center of focus. “You” is personal, immediate, powerful.

I come to this opinion both as an artist who uses words and as an old teacher of grammar and argumentative writing. In both cases, when writing fiction and writing to persuade someone of something, one has to always keep in mind one’s audience. This was always my first lesson to my students. They all understood instinctively that they were writing to persuade someone of something, but what they were actually doing was explaining things in their own words. They were writing down how they came to believe something. The point of argumentative writing, however, is to explain why someone else should believe something. And such writing changes depending on who you’re writing to, be it your writing teacher, a city council, your boss, or your mother. All argumentative writing has an inherent “you” at its core.

Fiction writing is similar, especially speculative fiction, the genre that I write. I may have a distinct image of a character in my head, but my job as a writer is to describe that character to someone else, i.e. the reader. I’ve written my fair share of short stories that made sense only to me, and while I really enjoy them and enjoy writing that way, a good story needs to be told so that the reader understands what is going on. Again, there is always a “you” at the core of fictional writing.

Very little fiction, however, is written in the second person. There are times, of course, when a “you” pops into the narration in a novel, but these are always surprising moments of breaking the fourth wall (there are some particularly powerful moments in Beowulf when this happens). Instead, a writer acts like a guide, showing the reader an imagined landscape before them, their arm on the reader’s shoulder, pointing out individual people and scenes and thoughts. Even still, that relationship between the artist and the reader is incredibly important.

There are some pieces of literature that are written entirely in the second person, the most famous being St. Augustine’s Confessions. Some claim that this is the first auto-biography ever written, though Augustine is constantly using the second person pronoun “you.” He’s not talking to the reader, though, but to God. The whole thing works as a kind of prayer (and, indeed, a confession) that Augustine addresses to God, and it is our privilege as readers to be invited into their intimate conversation. The book remains a piece of world-class literature, in part, because of the sense of love that Augustine shows for God and which is powerfully apparent in each and every word addressed to his beloved Lord.

There is another piece of artwork that is addressed to God and prayed in the second person, and that is the liturgy. The liturgy is one long prayer – or better said, it is a collection of prayers as one prayer, just as the Bible is a collection of books in one book. At times we speak to one another (as in “The Lord be with you” “And also with you”) or reading from Holy Scripture, but more often than not we are praying in the second person, together, to God in Jesus Christ.

Outside of church, we don’t speak as a group in the second person much at all. We speak as a group often, such as when we vote, but rarely do we speak as a group with “you.” The only time I can think of is in sports, when we cheer on a player or a team (this is especially true in baseball, where there is a sort of show-down between the pitcher and the batter). Communal prayer is special in this way, in that our individual voices are not lost in the group, nor is the group limited to a collection of individual voices but is more than a sum of its parts. Communal prayer is like sitting around a dinner table with family or friends and eating together, and communal prayer is complementing the chef with our hearts and our voices while enjoying the meal.

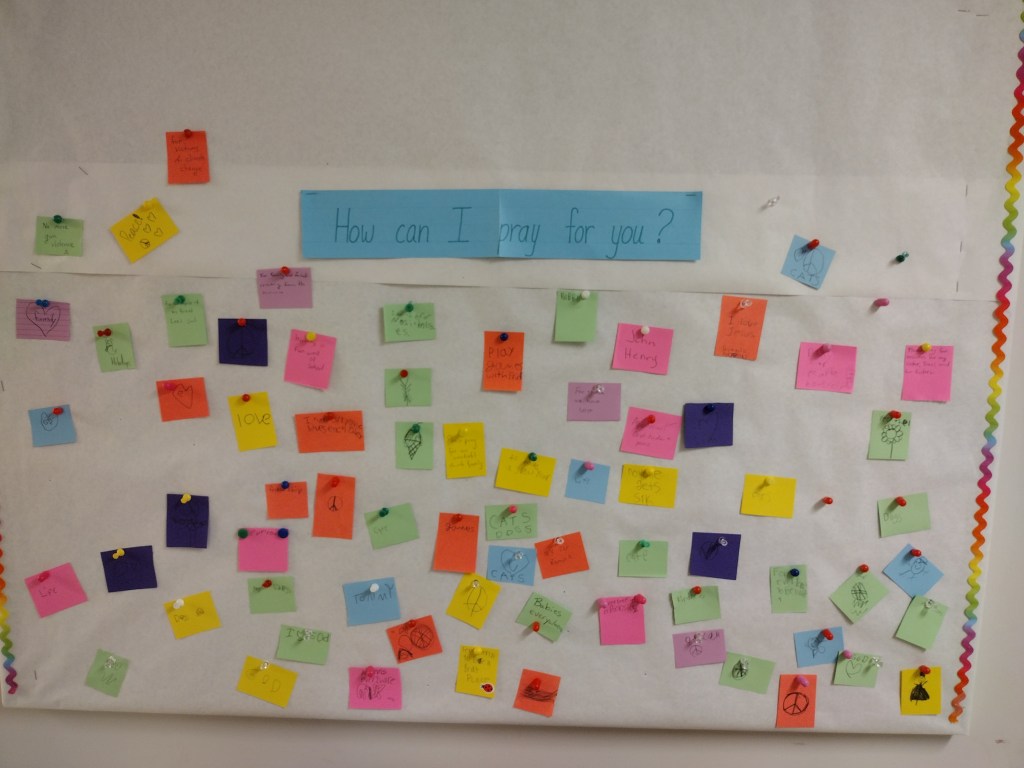

Second person “you” prayer, whether individual or communal, is kind of the opposite of keeping your audience in mind when writing argumentatively or with fiction. Instead of us putting our arm around our audience and pointing things out to them, God puts his arms around us as we point out things to him. We are safe in his arms as we discern the good and the bad in our lives, which is powerful enough individually, but is even more so in a group. Here, we tell God what is joyful and what is painful with our hearts joined together, so that our neighbor’s prayers become our prayers, and as we take up the weight of our neighbor’s sins and ask with them for forgiveness.

We often talk about “walking a mile in another person’s shoes”, but in communal, second person “you” prayer, we help carry another person’s cross. In many cases, we carry the other person as well. We don’t, however, just lift up a person’s cross or give them our shoulder, but we do these things in order that they might come closer to Jesus Christ, in whose presence is healing and joy beyond measure. In many ways, we give up some of the comfort of our lives in order to bring others to that healing. That’s part of what makes Christian prayer so powerful: it leaves the self behind so that we, empty, may carry the burdens of others to a specific place – and not just to a specific place, but to a specific person. A specific you.

I write all this about the liturgy, but it occurs in simple group prayer as well. Whenever two or three gather together in Jesus’ name, be that for a liturgical celebration or simply to pray for one another or even to enjoy one another’s company, Jesus is present among them. The special nature of the liturgy is that it encompasses every aspect of Christian vocation: prayer, Scripture, study, confession, reconciliation, a call to action – and Sacrament. That Sacrament, that great and blessed Eucharist, is itself an encapsulation of all that it means to be a Christian, from glory to humility (or one might say humiliation) of Jesus’ life, work, and hope for us humans. The liturgy is the Christian life.

And all of this, all of it, is directed towards a “you.” That relationship between the one who prays and God, in the context other others who are joined to us in prayer, is the most important relationship that we can ever find, in this life or in the next. Even the joy of calling God “you” extends beyond our human experience. We are drawn in by God’s arms when we direct our words to him, and we find our most intimate selves, either as individuals or as a community, when we look with our eyes and our hearts to God. “You” is like calling God “Abba, Father,” but even more intimately, even more powerfully, because it is so direct and so unattached to metaphors of God’s person. “You” is simply our effort to see God as who God is, not as we have imagined him. “You” avoids everything in the name of loving God and God alone, which mysteriously allows us to love everything other than God as well. “You” is a powerful word, a small and secret word, a holy and precious word.

Leave a comment