This year, I’ve taken on the discipline of bringing the Psalms more fully into my personal prayer life. Specifically, I’m making it a point to chant one psalm each day. I do this because, first, the Psalms are so very important to the Christian tradition and especially to the tradition of priestly prayer (to say nothing of monastic prayer!).

Also, quite simply, these are the songs of our people. I remember once, in seminary, we had a cross-religious worship service with a Muslim imam and a Jewish rabbi. Both the imam and the rabbi sung these beautiful songs in the traditional form of their religion. We Christians, on the other hand, sung Kumbaya. I had the distinct feeling during that prayer service that we Christians must have something more in our tradition than a campfire song from my childhood.

And we do! We have the Psalms! We have plainsong and Anglican chant and music in four-part harmony. There is music for most of the liturgy, and if I had my way (and a bit more ability in music), I’d sing the whole thing each and every Sunday. Religion is about music; music is about religion.

(As an aside, that’s one of the reasons why, in Tolkien’s creation myth, the universe is created by singing, by song)

But there’s also another reason why I’m focusing myself on the Psalms this year, and that’s because I feel some ambivalence towards them. There are some great Psalms, don’t get me wrong, but I have often felt that, more often than not, even the most beautiful prayers turn to vengeance. “Break the teeth in their mouth, O God,” sings Psalm 58. I do my best to forget what is done to baby’s heads in Psalm 137. For me, in most cases, the answer to violence is the Cross – in other words, blatant pacifism. We do not wish our enemies harm; we pray for them.

And so I thought, hey, if I’m uncomfortable with this part of my tradition, and especially if I’m uncomfortable about this part of the Bible, then I should spend a year praying with it and see what wisdom I am given by the Holy Spirit. So far, so good.

The only problem is that my two girls love praying with me, and they especially like it when I chant anything (I’m serious; I chanted a recipe in plainsong and they were delighted). It’s not that I’m a great singer. I’m not. I just think that my children love to see their father sing. They love being invited into that song, and they love just simply listening to me while they play with their toys on the couch beside me. And, to my surprise, they also really like how it sounds (I use a simpler version of what can be found here: click here). The opening to Sailor Moon, synth wave, and service music from the Hymnnal 1982, that’s what these kids like.

And here’s the problem: I can work through my own issues with the Psalms on my own; but what about chanting all those verses about vengeance with my children around? I preach about love all the time; what happens when they hear me chant about breaking the teeth in someone’s mouth? These are five- and eight-year old children. I really don’t want them to hear that kind of stuff, especially in religion, especially coming from their father’s mouth. And I’m certainly not going to tell them that they can’t pray with me. So, what do I do?

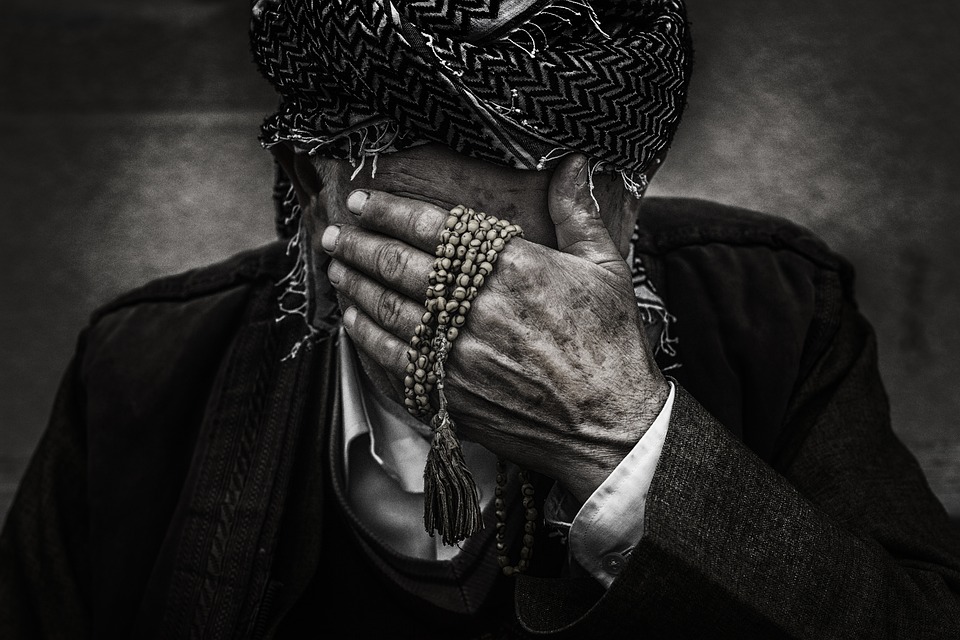

Well, I trust the Spirit. And when I trusted the Spirit, two things happened. First, I noticed nuances in the Psalms that I had never heard before. Yes, there’s a lot of vengeance in Psalm 7, but did you notice that in Psalm 9, where there is also a lot of vengeance, that violence is against those who oppress others? The Lord is a stronghold for the oppressed (v. 9); he does not forget the cry of the afflicted (v. 12). For the needy shall not always be forgotten, nor the hope of the poor perish forever (v. 18). This is the context of Psalm 9: not two people of equal power in an argument where no one is really right nor anyone is really wrong, but sung from the perspective of an embattled, downtrodden, oppressed, poor people struggling for justice. I had forgotten, somewhere along the way, that the Psalms were sung not by the kings of the world but by the little people stuck in between great empires.

These songs suddenly had a deeper meaning from me, specifically because I realized that the “I” in the Psalms was not me at all. It was from those I am called to serve. You see, I am a pretty privileged person. I’m white, male, middle-class, straight – the list goes on. I’m not oppressed. I have a funny nose, maybe, and I inherited a little bit of anxiety disorder, but that’s nothing compared to the weight of institutional and cultural oppression that presses on the shoulders and backs of culture groups like the ancient Jews (or modern Jews and Muslims, for that matter). The cries of the people in the Psalms were not idle complaints from a privileged guy living in a nice part of the United States; they were the calls that I specifically, as a privileged guy, was supposed to hear and to answer in the Holy Spirit. And to chant these songs in my own voice, to hear them coming from my own lips, made that call all the more pressing.

Then there’s the second thing that happened: I got to talk to my daughters about this wisdom that I was granted. My youngest daughter kind of checked out, but my oldest daughter (who is very sensitive to our call to love others) and I had a great conversation about bullying and caring for those who are made fun of. I got to remind her who God is: someone who answers our innermost pleas and frustrations. The oppressed have a voice in our religion, and it’s our job to hear that voice and to hear God’s call to us in it.

These are such important moments with kids. Certain lessons or individual moments might stick with them in their memory, but raising children is so much about providing a blanket or foundation of love, acceptance, and holiness in their lives. Especially as young girls who will eventually become women, I want them to understand where they have a voice and how people hear their voices. The Psalms is one of those places. So is their father and their mother. So are clergy and the people in the churches where they worship.

And the reason I’m writing this all to you isn’t just to talk about how interesting my prayer life is or how great my kids are, but to remind you that we have a responsibility to hear those voices in our churches or homes or communities that are crying out. We have a responsibility not just to our own prayer lives but also to be present to those growing up in our midst. That’s what it means, really, to belong to one another.

Leave a comment